This is a topic I got asked about a lot, even before coronavirus.

So many Bible stories touch on topics of illness and death, injustice, violence, and loss. How do we address these topics with children? And now, when illness and death, injustice, loss, disappointment, uncertainty, anxiety, and so much more have become more a part of our children’s daily lives than we wished, what do we do, as church leaders?

It feels false simply to cheerlead them through sessions about how happy we are because God loves us. In normal times, many children’s lives are not simple, straightforward, and happy, but now even the safest and most secure child is dealing with a world that may seem scary and chaotic. So we can’t just pretend everything is okay. But we don’t want to make things worse, or offer just doom and gloom. And of course it’s all harder in that much of this is happening over Zoom, instead of in person.

Here are a few tips from my own experiences. Please do add your own thoughts in the comments.

- Create space for conversation. Don’t fill the whole session with activities – allow room for discussion. Children will be bringing things to your session; experiences, questions, thoughts, and so on. Make room for that.

- Make the conversation open-ended and safe. Establish ground rules – “everyone’s ideas are okay.” This may mean you create a system for taking turns on Zoom (raising hands, reaction buttons) and you can make it routine that you mute yourself if you aren’t speaking. Use “I wonder …” questions. (“I wonder what your favourite part of the story was” / “I wonder what the most important part of the story was” / “I wonder what part of the story is for you” / “I wonder what Jesus’s friends felt when that happened” etc.)

- Use story. Often, people of all ages find it easier to talk about their own feelings if they have a story to talk about it through. Talking about how the characters feel, what the ending means, and so on, can help you talk about what’s going on in your own life, without revealing really personal stuff. A child who responds to the Baptism of Jesus story by saying “I liked when Jesus heard God’s voice, because maybe he’d been feeling really alone, but then he knew God was with him” may be saying something deeply personal, but because it’s done through the story, it’s easier to talk about. I’m making weekly story videos of the lectionary, which you can find here. If you’re dealing with a bereavement, I have a Pinterest board of children’s books about death, which can be found here.

- But also, allow children to process feelings in different ways. Some children will find it easier to express their emotions through drawing or making something. Some things I’ve done include, “make a Play-doh sculpture to show how the story made you feel,” “go find an object in your house that represents something that’s been sad or disappointing this year and we can pray about it,” and “draw what you’d like us to pray about.” Don’t force children to share their drawings/objects/etc if they don’t want to.

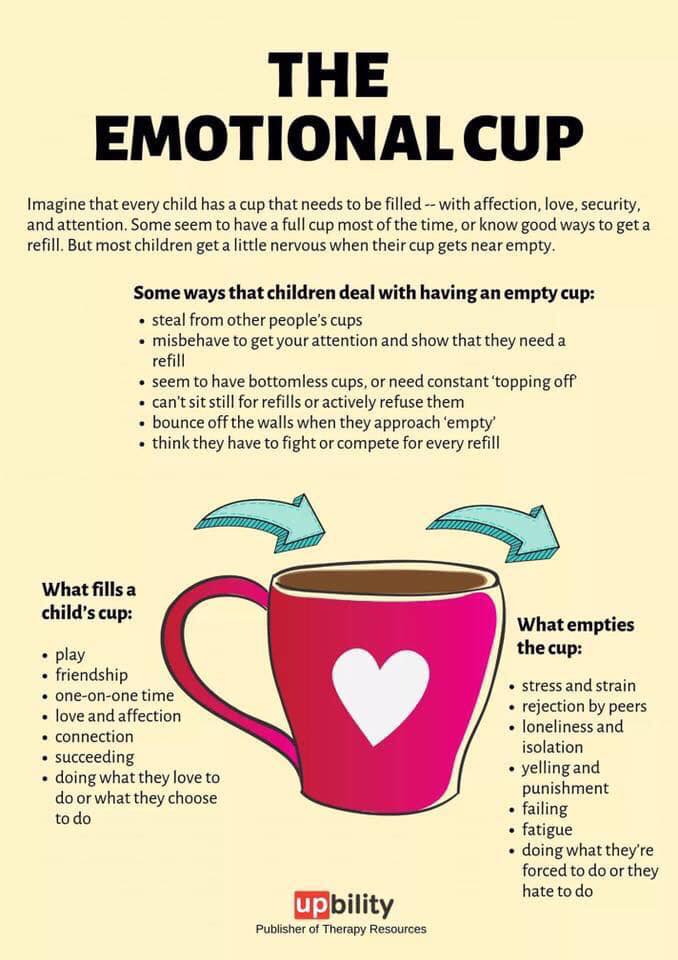

- Acknowledge emotions. We want to reassure children and make them feel safe, and this can sometimes lead us to dismiss what they’re feeling, if what they’re feeling is uncomfortable. If a child says “I feel like there’s no hope,” we want to instinctively say, “oh, I’m sure it isn’t that bad.” Unfortunately, that can lead the child to feel dismissed, and to trust us less. Acknowledging the feeling – “that sounds very hard. I’m so sorry you’re feeling that way. Thank you for telling us. Has anyone else in the group ever felt that way? What did you do that helped?” can acknowledge the emotion as real, while also pointing the child to look for coping mechanisms.

- Keep it small – that’s where the power is. “Can you think of one thing that made you smile this week, and say thank you to God for it?” “Can you think of three things you’re grateful for?” “What’s one thing you can do this week to help somebody else?” All of us, but children especially, feel better when we’re able to feel useful and helpful and like what we do matters. Giving children opportunities to reflect on gratitude and small blessings, and then to think of what they can do to make a difference, can be very helpful. This can be a way to close your prayer time.

Do you have any other thoughts on how to acknowledge difficult times and support children’s emotional wellbeing? Please share them in the comments!

partly from having read Lauren Winner’s excellent book Girl Meets God, which looks in detail at Ruth) was how this story provides a broad and inclusive model of what it means to be a family. It’s a step in the movement away from the purity model of the early patriarchs, when who your father was, and how cleanly your blood led you back to Abraham, was what mattered most, and towards Jesus’s model of, “those who follow my commandments are my family,” and the early church’s assertion that “there is no longer Jew nor Greek … all are one in Christ Jesus.”

partly from having read Lauren Winner’s excellent book Girl Meets God, which looks in detail at Ruth) was how this story provides a broad and inclusive model of what it means to be a family. It’s a step in the movement away from the purity model of the early patriarchs, when who your father was, and how cleanly your blood led you back to Abraham, was what mattered most, and towards Jesus’s model of, “those who follow my commandments are my family,” and the early church’s assertion that “there is no longer Jew nor Greek … all are one in Christ Jesus.”